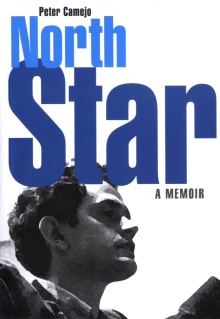

North Star – A Memoir

By Peter Camejo

Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2010

Peter Camejo was an important figure in the radicalisation of the 1960s and beyond, up to his untimely death in 2008. This book should be read by veterans of the socialist movement and wider social causes. It should also be read by new activists thirsty for understanding of previous struggles in order to better equip themselves for present and future battles.

Also, the book is a good read. The first chapter is set in 1979, out of chronological order from the rest of the book. It explains how the CIA attempted to get Peter arrested in Colombia, on a leg of a speaking tour in South America. If he had been imprisoned there it is possible that he would have been “disappeared”. Without giving away the story, Peter escaped this fate through an unlikely intervention, quite a tale in itself.

As Peter explains, the two of us met in college, collaborated and then joined the Socialist Workers Party at the same meeting in Boston in November 1959. I was 22 and Peter 20. We became leaders of the party’s associated youth group, the Young Socialist Alliance. In 1960 and 1961 a dispute over the Cuban Revolution broke out in the SWP and YSA. The majority in both groups supported the revolution and its leadership (with criticisms). Peter and I supported the majority position, and became its primary spokespersons in the YSA. As a result, I became the national chairperson and Peter the national secretary of the YSA and we moved to New York. Soon, along with others from a new generation, we joined with people from older generations in the leadership of the SWP.

Peter left the SWP in 1981. After that he remained active in various attempts to rebuild the US left, culminating in his running as the Green Party candidate for governor of California in 2002 and 2003, and then as independent candidate Ralph Nader’s running mate in the presidential elections of 2004.

Mass action

His experiences as a leader of the YSA and SWP, and his subsequent activities, form a major part of his memoir. In this review, I will concentrate on this aspect. There are three political threads that run through the book. One is that social change comes about through the action of masses of people. Related is the theme that attempts to circumvent mass action with the activities of small groups engaging in what they think of as “exemplary” actions of a few are an obstacle to social change. Two variants of this viewpoint are ultraleftism and sectarian abstention. The third theme is the need to break from the stranglehold of the parties of “money” as Peter puts it, the Democrats and Republicans.

Peter’s experiences as a leader in the anti-Vietnam War movement are vividly portrayed. One is his speaking before a crowd of 100,000 on the Boston Common as a spokesperson of the Student Mobilization Committee Against the War in Vietnam as part of the 1969 Vietnam Moratorium. There is a gripping account from a political opponent from the Democratic Party describing Peter as by far the best received speaker of the day. In fact, Peter was the best public speaker of our generation in the SWP and YSA, and, I think, of the youth radicalisation as a whole.

Peter had moved from New York to Berkeley, California, in late 1965, at the request of the SWP and YSA. The San Francisco Bay Area had become a centre of the new student movement, and the University of California at Berkeley especially so. Peter enrolled in the university, and quickly rose as a leader of the antiwar movement and the student movement there.

Competing perspectives

He outlines three different perspectives that emerged in the antiwar movement. One was that the movement should orient toward the Democratic Party. The Communist Party put forward this perspective, but also would endorse mass actions, especially during periods between elections. Another was associated with the national leaders of the Students for a Democratic Society, who, while calling for the first massive action in 1965, had subsequently turned their backs on mass action and increasingly championed small vanguard actions and then minority violence. The third approach, which we supported, was to further mass actions in the streets independent of both capitalist parties.

To do this, we focussed on building broad formations around the “single issue” of opposition to the war. All, regardless of their political views on other questions, were welcome to join. Within such coalitions, Peter explains, we argued for taking an “Out Now!” position, calling for immediate withdrawal from Vietnam. It took some years before “Out Now!” became the widely accepted goal of antiwar demonstrations.

Another key point we raised was non-exclusion. While independent of the Democrats and Republicans, we argued, the antiwar movement would welcome politicians from those parties who were against the war, on the principle that the movement had to be non-exclusionary. In practice, there were very few such politicians. It was on this basis that the large antiwar demonstrations that reached into the hundreds of thousands were organised.

An aspect of our approach was to build antiwar committees both locally and nationally by putting decision making in the hands of the activists themselves. Votes would be taken by the assembled activists after open debate. Most often our mass action perspective would carry the day, which led many others with opposing perspectives to charge that we had mechanical majorities of our own members at such meetings. But we never became anywhere near that large, although we did grow substantially during this period. Our arguments simply made sense to the majority of antiwar activists. This approach also raised the self-confidence of the participants, who became more dedicated to building the mass actions as a result.

Peter concludes that the SWP played a crucial and positive role in the antiwar movement. Peter himself was an important part of that effort.

Berkeley battle

There is a riveting chapter on what became known as “the battle of Telegraph Avenue”. This street abutted the university campus. In May-June 1968 there was a massive student-worker uprising in France which galvanised the world. Our young French co-thinkers played an important part in these events. We organised support meetings and picket demonstrations in solidarity. In Berkeley, Peter met with other campus leaders to organise a big meeting on Telegraph Avenue. The SWP and YSA reached out to involve other organisations, but Peter was recognised as the main leader of the event.

The rally was set for June 28. The Berkeley City Council voted down the organisers’ request to shut down a short stretch of the avenue next to the campus for the event. So there was agreement that the participants would stay on the footpaths. Monitors were stationed to help keep the crowd on the footpaths. But then the police attacked.

The students fought back as best they could. The next days and nights were marked by increased police violence; all of the city of Berkeley was placed on night-time curfew; there were mass meetings of the young people who fought against these violations of their rights to free speech and assembly. Finally, the city backed down and allowed the rally to proceed on Telegraph Avenue on July 4.

Peter’s account of how this victory was won makes for exciting reading, but more important are the lessons to be drawn. There was a big difference between the physical showdown between the mass of student protesters and the cops, and the actions of violence, even bombings, carried out by small groups believing they were “sparking” the mass movement. In contrast to such futile “offensive” actions, the protesters of Telegraph Avenue were defending their fundamental rights. All of their decisions were made at mass meetings after open debate. Their most important decision was to defy the city authorities by holding a rally on July 4, come what may. They knew that this could mean a violent confrontation with the police. They had already suffered casualties, and understood what this could mean. It was this resolve that forced the city council to back down.

An important aspect of the leadership of the SWP and YSA and Peter himself was to reach out to the citizens of Berkeley: the fight for public opinion. Initially, this was against the students. But through careful tactics aimed at bringing the truth of the situation to the public, that the city authorities were trampling on rights guaranteed in the US Constitution, the mood in the city swung over to support them. The over-reaction of the police, attacking bystanders and even people in their homes, was a factor. Police always go too far in such situations, but this truth had to made widely known.

In every way, Peter’s leadership was geared toward mass mobilisation and mass action.

Two-party system

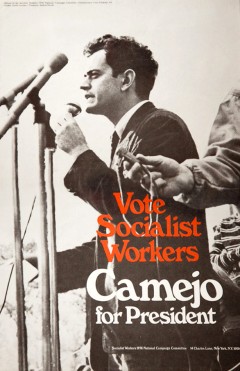

The third thread that runs through the book from beginning to end is the need to break from the Democratic and Republican parties. This was an aspect of our insistence that the antiwar movement be focussed on independent mass actions in the streets, not subordinate in any way to the twin parties of “money”. It was projected in the small example set by SWP election campaigns, from the first one Peter and I participated in, Farrell Dobbs' 1960 presidential campaign with Myra Tanner Weiss as his running mate, through Peter’s own campaigns for mayor of Berkeley, US senator from Massachusetts and his 1976 campaign for president with running mate Willie May Reid. After he left the SWP, Peter supported the independent campaigns of the Green Party, including Ralph Nader’s 2000 run for president, and ran for governor of California in 2002 and 2003, and as independent Ralph Nader’s running mate in 2004.

Green Party

Peter’s last battle was to keep the Green Party independent from the Democrats, a fight which he lost at the national level, as is well documented in the book, although some local Green Party groups do maintain their independence.

A comment is in order here. There are splinters of the Trotskyist movement who have attacked Peter’s support of independent Green Party election campaigns. Their argument is that the Greens are not a socialist party, nor do they have a base in the trade unions. These groups (including the rump which still uses the SWP name) say they would vote for a Labor Party if the trade unions organised one, claiming that it would be a workers’ party. They point to Lenin’s position in 1919 that the newly formed British Communist Party should vote for the Labour Party. They leave out that Lenin also said that the British Labour Party was a bourgeois party through and through, and an imperialist party to boot. He urged the young CP to vote for this imperialist capitalist party anyway, to reach out to the British workers whose trade unions had created it. The weird logic of the sectarian argument ends up urging a vote for the Labour Party of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, while opposing a vote for the anti-imperialist, pro-working class Ralph Nader. It is true that the US Green Party is a petty-bourgeois (and thus bourgeois) party, but it is not a party of the big bourgeoisie nor is it an imperialist party. Unfortunately, on a national level it is now on a slippery slope towards supporting the imperialist Democratic Party. In many countries, the Greens have already gone over to finance capital.

A bright spot Peter points to was the 2000 campaign of Nader for president on the Green Party ticket. Tens of thousands packed Nader rallies in many cities, more than those of the two capitalist parties. These rallies were mainly young. A central aspect, evident in the shouts and applause of these young people, was their identification with the big anti-globalisation demonstration in Seattle the year before. A new movement had appeared, inexperienced, new to radical ideas, but moving in an anti-capitalist direction – and full of the energy and enthusiasm of youth. Peter doesn’t mention this background to the Nader campaign, but this must be an oversight.

We both were present at the Oakland, California, Nader rally and saw these anti-globalisation young people first hand. Nader reacted to the shouts of the crowd, absorbing their energy, and his speech became more and more radical, which furthered the excitement of the audience.

This anti-globalisation movement was cut short by the chauvinism and warmongering whipped up by the Bush administration, the Congress to a person and the press after 9/11. The movement continued elsewhere, but was silenced in the US. This was the major factor in the success of the subsequent Democratic Party anti-Nader campaign that reached into the Green Party itself. Figures like Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Media Benjamin and Michael Moore capitulated. Not content with only their ideological campaign, the Democrats launched a series of despicable dirty tricks to keep the Nader-Camejo ticket off the ballot. This part of Peter’s book graphically explains the obstacles we face in breaking the two-party stranglehold.

Jesse Jackson campaign

Peter writes that in 1984 he made a “major political mistake” in supporting the campaign by Jesse Jackson in the Democratic Party presidential primaries. A detail that Peter omits was that after Jackson lost, Peter supported the Democratic candidate Walter Mondale in the general election. After Peter left the SWP in 1981, I hadn’t had contact with him. In 1984, I happened to be walking by a Mondale street rally in New York, and ran into Peter, who handed me a vote Mondale leaflet. This seemed to me at the time to validate charges by the SWP leadership that Peter had moved way to the right.

Later, Peter and I talked about this. He said he wrongly supported the Mondale campaign as part of his tactic of trying to work within Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition in hopes that it would lead to a mass break with the Democrats. Peter writes: “This error on my part lasted until I came to my senses and realized that, with few exceptions, the Rainbow Coalition was just another name for keeping progressives in the Democratic Party”.

An important appendix is a short essay on the origins and history of the two-party system. He shows that the present Republican and Democratic parties emerged from a single party, the Republicans, after the Civil War. This appendix should be reprinted as a pamphlet for the new generations who will become radicalised in the future.

There is a chapter on how Peter became a stockbroker, and how he helped set up a firm, Progressive Assets Management. The idea was that Peter would invest money for those who didn’t want to invest in firms doing business in apartheid South Africa, polluters and so forth. There was an element of self-deception in this undertaking, as the control of the economy by financial capital makes it virtually impossible to know where investments go, except for some start-ups like solar power firms. This chapter is interesting, however, in explaining the obstacles the powers that be put in the way of Peter’s progressive projects. His outline of how workers’ pension funds are controlled by capital is revealing.

Changing view of program

When my companion, Caroline Lund, and I reconnected with Peter, it was some years after we had left the SWP. We had moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. It was in the early 1990s when we first talked. In discussing what had happened to the SWP, Peter said that the fundamental question was that the program of the SWP was wrong. Since this theme is a major one in his book book, and since I disagree with him, I will take this up in some detail, both to disclose my bias and to explain Peter’s views in the latter part of his life more clearly.

Peter told me this disagreement represented a “profound difference” between us. I agree.

Vote Socialist Workers – Camejo for President

Vote Socialist Workers – Camejo for President